It’s an understatement that the way we dress has changed a lot in the last couple of centuries. In some ways it has gotten better, less rules to follow and a freedom to express the individuality through the different tastes and styles that each and everyone of us prefer. However, we could all learn a couple of things from our ancestors regarding the etiquette rules of dressing properly.

In year 1960 Cecil B. Hartley published the book The Gentlemen’s Book of Etiquette in which a whole chapter is dedicated to the art of dressing according to the etiquette rules. You may notice that a few things have changed since then, and as mentioned, not always for the better.

Here is the chapter about how to dress like a gentleman:

CHAPTER VII.

DRESS.

From the book THE GENTLEMEN’S BOOK OF ETIQUETTE, AND MANUAL OF POLITENESS by CECIL B. HARTLEY.

Between the sloven and the coxcomb there is generally a competition which shall be the more contemptible: the one in the total neglect of every thing which might make his appearance in public supportable, and the other in the cultivation of every superfluous ornament. The former offends by his negligence and dirt, and the latter by his finery and perfumery. Each entertains a supreme contempt for the other, and while both are right in their opinion, both are wrong in their practice. It is not in either extreme that the man of real elegance and refinement will be shown, but in the happy medium which allows taste and judgment to preside over the wardrobe and toilet-table, while it prevents too great an attention to either, and never allows personal appearance to become the leading object of life.

The French have a proverb, “It is not the cowl which makes the monk,” and it might be said with equal truth, “It is not the dress which makes the gentleman,” yet, as the monk is known abroad by his cowl, so the true gentleman will let the refinement of his mind and education be seen in his dress.

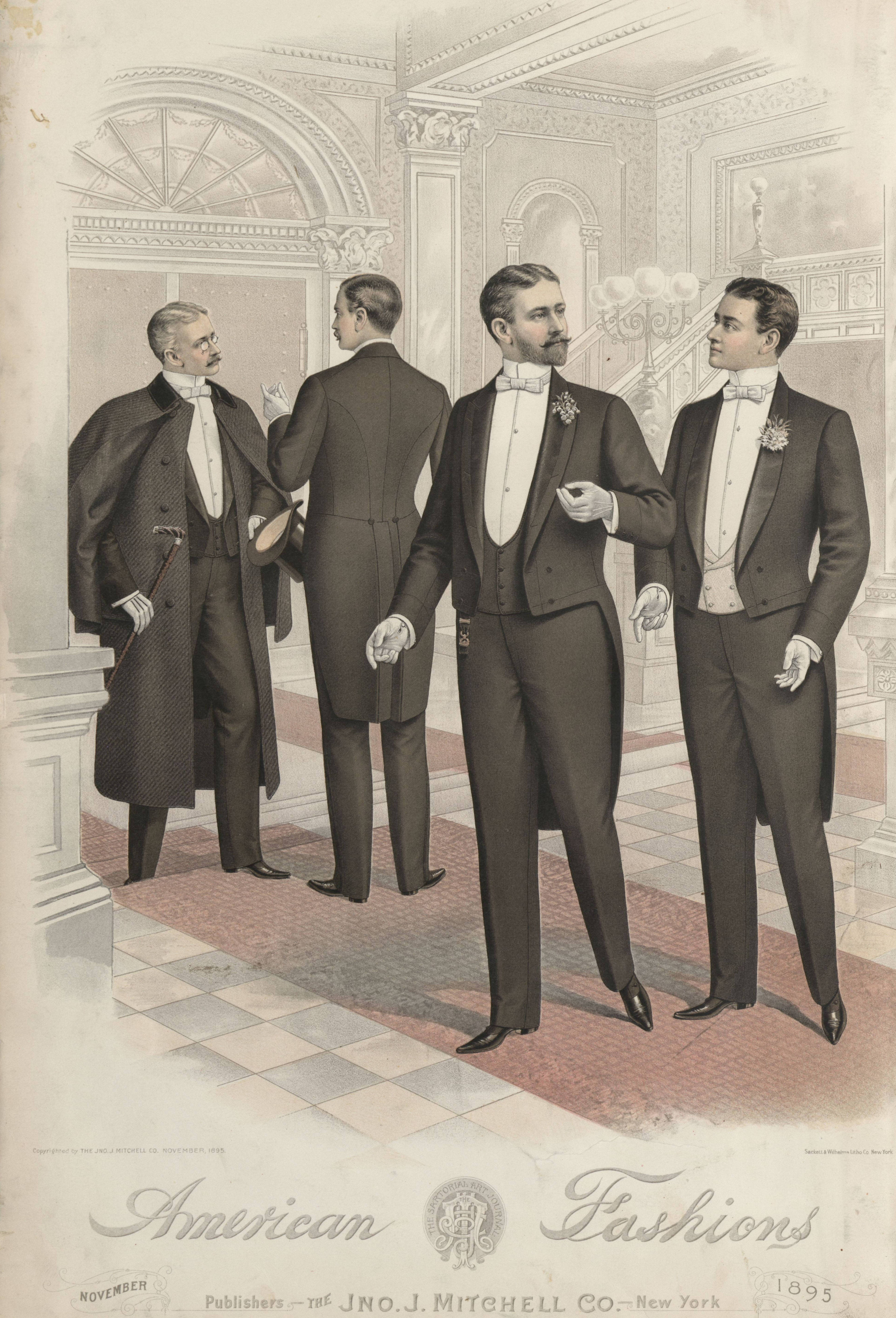

The first rule for the guidance of a man, in matters of dress, should be, “Let the dress suit the occasion.” It is as absurd for a man to go into the street in the morning with his dress-coat, white kid gloves, and dancing-boots, as it would be for a lady to promenade the fashionable streets, in full evening dress, or for the same man to present himself in the ball-room with heavy walking-boots, a great coat, and riding-cap.

It is true that there is little opportunity for a gentleman to exercise his taste for coloring, in the black and white dress which fashion so imperatively declares to be the proper dress for a dress occasion. He may indulge in light clothes in the street during the warm months of the year, but for the ball or evening party, black and white are the only colors (or no colors) admissible, and in the midst of the gay dresses of the ladies, the unfortunate man in his sombre dress appears like a demon who has found his way into Paradise among the angels. N’importe! Men should be useful to the women, and how can they be better employed than acting as a foil for their loveliness of face and dress!

Notwithstanding the dress, however, a man may make himself agreeable, even in the earthly Paradise, a ball-room. He can rise above the mourning of his coat, to the joyousness of the occasion, and make himself valued for himself, not his dress. He can make himself admired for his wit, not his toilette; his elegance and refinement, not the price of his clothes.

There is another good rule for the dressing-room: While you are engaged in dressing give your whole attention to it. See that every detail is perfect, and that each article is neatly arranged. From the curl ofyour hair to the tip of your boot, let all be perfect in its make and arrangement, but, as soon as you have left your mirror, forget your dress. Nothing betokens the coxcomb more decidedly than to see a man always fussing about his dress, pulling down his wristbands, playing with his moustache, pulling up his shirt collar, or arranging the bow of his cravat. Once dressed, do not attempt to alter any part of your costume until you are again in the dressing-room.

In a gentleman’s dress any attempt to be conspicuous is in excessively bad taste. If you are wealthy, let the luxury of your dress consist in the fine quality of each article, and in the spotless purity of gloves and linen, but never wear much jewelry or any article conspicuous on account of its money value. Simplicity should always preside over the gentleman’s wardrobe.

Follow fashion as far as is necessary to avoid eccentricity or oddity in your costume, but avoid the extreme of the prevailing mode. If coats are worn long, yours need not sweep the ground, if they are loose, yours may still have some fitness for your figure; if pantaloons are cut large over the boot, yours need not cover the whole foot, if they are tight, you may still take room to walk. Above all, let your figure and style of face have some weight in deciding how far you are to follow fashion. For a very tall man to wear a high, narrow-brimmed hat, long-tailed coat, and tight pantaloons, with a pointed beard and hair brushed up from the forehead, is not more absurd than for a short, fat man, to promenade the street in a low, broad-brimmed hat, loose coat and pants, and the latter made of large plaid material, and yet burlesques quite as broad may be met with every day.

An English writer, ridiculing the whims of Fashion, says:—

“To be in the fashion, an Englishman must wear six pairs of gloves in a day:

“In the morning, he must drive his hunting wagon in reindeer gloves.

“In hunting, he must wear gloves of chamois skin.

“To enter London in his tilbury, beaver skin gloves.

“Later in the day, to promenade in Hyde Park, colored kid gloves, dark.

“When he dines out, colored kid gloves, light.

“For the ball-room, white kid gloves.”

Thus his yearly bill for gloves alone will amount to a most extravagant sum.

In order to merit the appellation of a well-dressed man, you must pay attention, not only to the more prominent articles of your wardrobe, coat, pants, and vest, but to the more minute details. A shirtfront which fits badly, a pair of wristbands too wide or too narrow, a badly brushed hat, a shabby pair of gloves, or an ill-fitting boot, will spoil the most elaborate costume. Purity of skin, teeth, nails; well brushed hair; linen fresh and snowy white, will make clothes of the coarsest material, if well made, look more elegant, than the finest material of cloth, if these details are neglected.

Frequent bathing, careful attention to the teeth, nails, ears, and hair, are indispensable to a finished toilette.

Use but very little perfume, much of it is in bad taste.

Let your hair, beard, and moustache, be always perfectly smooth, well arranged, and scrupulously clean.

It is better to clean the teeth with a piece of sponge, or very soft brush, than with a stiff brush, and there is no dentifrice so good as White Castile Soap.

Wear always gloves and boots, which fit well and are fresh and whole. Soiled or torn gloves and boots ruin a costume otherwise faultless.

Extreme propriety should be observed in dress. Be careful to dress according to your means. Too great saving is meanness, too great expense is extravagance.

A young man may follow the fashion farther than a middle-aged or elderly man, but let him avoid going to the extreme of the mode, if he would not be taken for an empty headed fop.

It is best to employ a good tailor, as a suit of coarse broadcloth which fits you perfectly, and is stylish in cut, will make a more elegant dress than the finest material badly made.

Avoid eccentricity; it marks, not the man of genius, but the fool.

A well brushed hat, and glossy boots must be always worn in the street.

White gloves are the only ones to be worn with full dress.

A snuff box, watch, studs, sleeve-buttons, watch-chain, and one ring are all the jewelry a well-dressed man can wear.

An English author, in a recent work, gives the following rules for a gentleman’s dress:

“The best bath for general purposes, and one which can do little harm, and almost always some good, is a sponge bath. It should consist of a large, flat metal basin, some four feet in diameter, filled with cold water. Such a vessel may be bought for about fifteen shillings. A large, coarse sponge—the coarser the better—will cost another five or seven shillings, and a few Turkish towels complete the ‘properties.’ The water should be plentiful and fresh, that is, brought up a little while before the bath is to be used; not placed over night in the bed-room. Let us wash and be merry, for we know not how soon the supply of that precious article which here costs nothing may be cut off. In many continental towns they buy their water, and on a protracted sea voyage the ration is often reduced to half a pint a day for all purposes, so that a pint per diem is considered luxurious. Sea-water, we may here observe, does not cleanse, and a sensible man who bathes in the sea will take a bath of pure water immediately after it. This practice is shamefully neglected, and I am inclined to think that in many cases a sea-bath will do more harm than good without it, but, if followed by a fresh bath, cannot but be advantageous.

“Taking the sponge bath as the best for ordinary purposes, we must point out some rules in its use. The sponge being nearly a foot in length, and six inches broad, must be allowed to fill completely with water, and the part of the body which should be first attacked is the stomach. It is there that the most heat has collected during the night, and the application of cold water quickens the circulation at once, and sends the blood which has been employed in digestion round the whole body. The head should next be soused, unless the person be of full habit, when the head should be attacked before the feet touch the cold water at all. Some persons use a small hand shower bath, which is less powerful than the common shower bath, and does almost as much good. The use of soap in the morning bath is an open question. I confess a preference for a rough towel, or a hair glove. Brummell patronized the latter, and applied it for nearly a quarter of an hour every morning.

“The ancients followed up the bath by anointing the body, and athletic exercises. The former is a mistake; the latter, an excellent practice, shamefully neglected in the present day. It would conduce much to health and strength if every morning toilet comprised the vigorous use of the dumb-bells, or, still better, the exercise of the arms without them. The best plan of all is, to choose some object in your bed-room on which to vent your hatred, and box at it violently for some ten minutes, till the perspiration covers you. The sponge must then be again applied to the whole body. It is very desirable to remain without clothing as long as possible, and I should therefore recommend that every part of the toilet which can conveniently be performed without dressing, should be so.

“The next duty, then, must be to clean the Teeth. Dentists are modern inquisitors, but their torture-rooms are meant only for the foolish. Everybody is born with good teeth, and everybody might keep them good by a proper diet, and the avoidance of sweets and smoking. Of the two the former are, perhaps, the more dangerous. Nothing ruins the teeth so soon as sugar in one’s tea, and highly sweetened tarts and puddings, and as it is le premier pas qui coûte, these should be particularly avoided in childhood. When the teeth attain their full growth and strength it takes much more to destroy either their enamel or their substance.

“It is upon the teeth that the effects of excess are first seen, and it is upon the teeth that the odor of the breath depends. If I may not say that it is a Christian duty to keep your teeth clean, I may, at least, remind you that you cannot be thoroughly agreeable without doing so. Let words be what they may, if they come with an impure odor, they cannot please. The butterfly loves the scent of the rose more than its honey.

“The teeth should be well rubbed inside as well as outside, and the back teeth even more than the front. The mouth should then be rinsed, if not seven times, according to the Hindu legislator, at least several times, with fresh, cold water. This same process should be repeated several times a day, since eating, smoking, and so forth, naturally render the teeth and mouth dirty more or less, and nothing can be so offensive, particularly to ladies, whose sense of smell seems to be keener than that of the other sex, and who can detect at your first approach whether you have been drinking or smoking. But, if only for your own comfort, you should brush your teeth both morning and evening, which is quite requisite for the preservation of their soundness and color; while, if you are to mingle with others, they should be brushed, or, at least, the mouth well rinsed after every meal, still more after smoking, or drinking wine, beer, or spirits. No amount of general attractiveness can compensate for an offensive odor in the breath; and none of the senses is so fine a gentleman, none so unforgiving, if offended, as that of smell.

“Strict attention must be paid to the condition of the nails, and that both as regards cleaning and cutting. The former is best done with a liberal supply of soap on a small nail-brush, which should be used before every meal, if you would not injure your neighbor’s appetite. While the hand is still moist, the point of a small pen-knife or pair of stumpy nail-scissors should be passed under the nails so as to remove every vestige of dirt; the skin should be pushed down with a towel, that the white half-moon may be seen, and the finer skin removed with the knife or scissors. Occasionally the edges of the nails should be filed, and the hard skin which forms round the corners of them cut away. The important point in cutting the nails is to preserve the beauty of their shape. That beauty, even in details, is worth preserving, I have already remarked, and we may study it as much in paring our nails, as in the grace of our attitudes, or any other point. The shape, then, of the nail should approach, as nearly as possible, to the oblong. The length of the nail is an open question. Let it be often cut, but always long, in my opinion. Above all, let it be well cut, and never bitten.

“Perhaps you tell me these are childish details. Details, yes, but not childish. The attention to details is the true sign of a great mind, and he who can in necessity consider the smallest, is the same man who can compass the largest subjects. Is not life made up of details? Must not the artist who has conceived a picture, descend from the dream of his mind to mix colors on a palette? Must not the great commander who is bowling down nations and setting up monarchies care for the health and comfort, the bread and beef of each individual soldier? I have often seen a great poet, whom I knew personally, counting on his fingers the feet of his verses, and fretting with anything but poetic language, because he could not get his sense into as many syllables. What if his nails were dirty? Let genius talk of abstract beauty, and philosophers dogmatize on order. If they do not keep their nails clean, I shall call them both charlatans. The man who really loves beauty will cultivate it in everything around him. The man who upholds order is not conscientious if he cannot observe it in his nails. The great mind can afford to descend to details; it is only the weak mind that fears to be narrowed by them. When Napoleon was at Munich he declined the grand four-poster of the Witelsbach family, and slept, as usual, in his little camp-bed. The power to be little is a proof of greatness.

“For the hands, ears, and neck we want something more than the bath, and, as these parts are exposed and really lodge fugitive pollutions, we cannot use too much soap, or give too much trouble to their complete purification. Nothing is lovelier than a woman’s small, white, shell-like ear; few things reconcile us better to earth than the cold hand and warm heart of a friend; but, to complete the charm, the hand should be both clean andsoft. Warm water, a liberal use of the nail-brush, and no stint of soap, produce this amenity far more effectually than honey, cold cream, and almond paste. Of wearing gloves I shall speak elsewhere, but for weak people who are troubled with chilblains, they are indispensable all the year round. I will add a good prescription for the cure of chilblains, which are both a disfigurement, and one of the petites misères of human life.

“‘Roll the fingers in linen bandages, sew them up well, and dip them twice or thrice a day in a mixture, consisting of half a fluid ounce of tincture of capsicum, and a fluid ounce of tincture of opium.’

“The person who invented razors libelled Nature, and added a fresh misery to the days of man.

“Whatever Punch may say, the moustache and beard movement is one in the right direction, proving that men are beginning to appreciate beauty and to acknowledge that Nature is the best valet. But it is very amusing to hear men excusing their vanity on the plea of health, and find them indulging in the hideous ‘Newgate frill’ as a kind of compromise between the beard and the razor. There was a time when it was thought a presumption and vanity to wear one’s own hair instead of the frightful elaborations of the wig-makers, and the false curls which Sir Godfrey Kneller did his best to make graceful on canvas. Who knows that at some future age some Punch of the twenty-first century may not ridicule the wearing of one’s own teeth instead of the dentist’s? At any rate Nature knows best, and no man need be ashamed of showing his manhood in the hair of his face. Of razors and shaving, therefore, I shall only speak from necessity, because, until everybody is sensible on this point, they will still be used.

“Napoleon shaved himself. ‘A born king,’ said he, ‘has another to shave him. A made king can use his own razor.’ But the war he made on his chin was very different to that he made on foreign potentates. He took a very long time to effect it, talking between whiles to his hangers-on. The great man, however, was right, and every sensible man will shave himself, if only as an exercise of character, for a man should learn to live, in every detail without assistance. Moreover, in most cases, we shave ourselves better than barbers can do. If we shave at all, we should do it thoroughly, and every morning. Nothing, except a frown and a hay-fever, makes the face look so unlovely as a chin covered with short stubble. The chief requirements are hot water, a large, soft brush of badger hair, a good razor, soft soap that will not dry rapidly, and a steady hand. Cheap razors are a fallacy. They soon lose their edge, and no amount of stropping will restore it. A good razor needs no strop. If you can afford it, you should have a case of seven razors, one for each day of the week, so that no one shall be too much used. There are now much used packets of papers of a certain kind on which to wipe the razor, and which keep its edge keen, and are a substitute for the strop.

“Beards, moustaches, and whiskers, have always been most important additions to the face. In the present day literary men are much given to their growth, and in that respect show at once their taste and their vanity. Let no man be ashamed of his beard, if it be well kept and not fantastically cut. The moustache should be kept within limits. The Hungarians wear it so long that they can tie the ends round their heads. The style of the beard should be adopted to suit the face. A broad face should wear a large, full one; a long face is improved by a sharp-pointed one. Taylor, the water poet, wrote verses on the various styles, and they are almost numberless. The chief point is to keep the beard well-combed and in neat trim.

“As to whiskers, it is not every man who can achieve a pair of full length. There is certainly a great vanity about them, but it may be generally said that foppishness should be avoided in this as in most other points. Above all, the whiskers should never be curled, nor pulled out to an absurd length. Still worse is it to cut them close with the scissors. The moustache should be neat and not too large, and such fopperies as cutting the points thereof, or twisting them up to the fineness of needles—though patronized by the Emperor of the French—are decidedly a proof of vanity. If a man wear the hair on his face which nature has given him, in the manner that nature distributes it, keeps it clean, and prevents its overgrowth, he cannot do wrong. All extravagances are vulgar, because they are evidence of a pretence to being better than you are; but a single extravagance unsupported is perhaps worse than a number together, which have at least the merit of consistency. If you copy puppies in the half-yard of whisker, you should have their dress and their manner too, if you would not appear doubly absurd.

{129}“The same remarks apply to the arrangement of the hair in men, which should be as simple and as natural as possible, but at the same time a little may be granted to beauty and the requirements of the face. For my part I can see nothing unmanly in wearing long hair, though undoubtedly it is inconvenient and a temptation to vanity, while its arrangement would demand an amount of time and attention which is unworthy of a man. But every nation and every age has had a different custom in this respect, and to this day even in Europe the hair is sometimes worn long. The German student is particularly partial to hyacinthine locks curling over a black velvet coat; and the peasant of Brittany looks very handsome, if not always clean, with his love-locks hanging straight down under a broad cavalier hat. Religion has generally taken up the matter severely. The old fathers preached and railed against wigs, the Calvinists raised an insurrection in Bordeaux on the same account, and English Roundheads consigned to an unmentionable place every man who allowed his hair to grow according to nature. The Romans condemned tresses as unmanly, and in France in the middle ages the privilege to wear them was confined to royalty. Our modern custom was a revival of the French revolution, so that in this respect we are now republican as well as puritanical.

“If we conform to fashion we should at least make the best of it, and since the main advantage of short hair is its neatness, we should take care to keep ours neat. This should be done first by frequent visits to the barber, for if the hair is to be short at all it should be very short, and nothing looks more untidy than long, stiff, uncurledmasses sticking out over the ears. If it curls naturally so much the better, but if not it will be easier to keep in order. The next point is to wash the head every morning, which, when once habitual, is a great preservative against cold. A pair of large brushes, hard or soft, as your case requires, should be used, not to hammer the head with, but to pass up under the hair so as to reach the roots. As to pomatum, Macassar, and other inventions of the hair-dresser, I have only to say that, if used at all, it should be in moderation, and never sufficiently to make their scent perceptible in company. Of course the arrangement will be a matter of individual taste, but as the middle of the hair is the natural place for a parting, it is rather a silly prejudice to think a man vain who parts his hair in the centre. He is less blamable than one who is too lazy to part it at all, and has always the appearance of having just got up.

“Of wigs and false hair, the subject of satires and sermons since the days of the Roman Emperors, I shall say nothing here except that they are a practical falsehood which may sometimes be necessary, but is rarely successful. For my part I prefer the snows of life’s winter to the best made peruke, and even a bald head to an inferior wig.

“When gentlemen wore armor, and disdained the use of their legs, an esquire was a necessity; and we can understand that, in the days of the Beaux, the word “gentleman” meant a man and his valet. I am glad to say that in the present day it only takes one man to make a gentleman, or, at most, a man and a ninth—that is, including the tailor. It is an excellent thing{131} for the character to be neat and orderly, and, if a man neglects to be so in his room, he is open to the same temptation sooner or later in his person. A dressing-case is, therefore, a desideratum. A closet to hang up cloth clothes, which should never be folded, and a small dressing-room next to the bed-room, are not so easily attainable. But the man who throws his clothes about the room, a boot in one corner, a cravat in another, and his brushes anywhere, is not a man of good habits. The spirit of order should extend to everything about him.

“This brings me to speak of certain necessities of dress; the first of which I shall take is appropriateness. The age of the individual is an important consideration in this respect; and a man of sixty is as absurd in the style of nineteen as a young man in the high cravat of Brummell’s day. I know a gallant colonel who is master of the ceremonies in a gay watering-place, and who, afraid of the prim old-fashioned tournureof his confrères in similar localities, is to be seen, though his hair is gray and his age not under five-and-sixty, in a light cut-away, the ‘peg-top’ continuations, and a turned-down collar. It may be what younger blades will wear when they reach his age, but in the present day the effect is ridiculous. We may, therefore, give as a general rule, that after the turning-point of life a man should eschew the changes of fashion in his own attire, while he avoids complaining of it in the young. In the latter, on the other hand, the observance of these changes must depend partly on his taste and partly on his position. If wise, he will adopt with alacrity any new fashions which improve the grace, the ease, the healthfulness, and the convenience of his garments. He will be glad of greater freedom in the cut of his cloth clothes, of boots with elastic sides instead of troublesome buttons or laces, of the privilege to turn down his collar, and so forth, while he will avoid as extravagant, elaborate shirt-fronts, gold bindings on the waistcoat, and expensive buttons. On the other hand, whatever his age, he will have some respect to his profession and position in society. He will remember how much the appearance of the man aids a judgment of his character, and this test, which has often been cried down, is in reality no bad one; for a man who does not dress appropriately evinces a want of what is most necessary to professional men—tact and discretion.

“Position in society demands appropriateness. Well knowing the worldly value of a good coat, I would yet never recommend a man of limited means to aspire to a fashionable appearance. In the first place, he becomes thereby a walking falsehood; in the second, he cannot, without running into debt, which is another term for dishonesty, maintain the style he has adopted. As he cannot afford to change his suits as rapidly as fashion alters, he must avoid following it in varying details. He will rush into wide sleeves one month, in the hope of being fashionable, and before his coat is worn out, the next month will bring in a narrow sleeve. We cannot, unfortunately, like Samuel Pepys, take a long cloak now-a-days to the tailor’s, to be cut into a short one, ‘long cloaks being now quite out,’ as he tells us. Even when there is no poverty in the case, our position must not be forgotten. The tradesman will win neither customers nor friends by adorning himself in the mode of the club-lounger,{133} and the clerk, or commercial traveler, who dresses fashionably, lays himself open to inquiries as to his antecedents, which he may not care to have investigated. In general, it may be said that there is vulgarity in dressing like those of a class above us, since it must be taken as a proof of pretension.

“As it is bad taste to flaunt the airs of the town among the provincials, who know nothing of them, it is worse taste to display the dress of a city in the quiet haunts of the rustics. The law, that all attempts at distinction by means of dress is vulgar and pretentious, would be sufficient argument against wearing city fashions in the country.

“While in most cases a rougher and easier mode of dress is both admissible and desirable in the country, there are many occasions of country visiting where a town man finds it difficult to decide. It is almost peculiar to the country to unite the amusements of the daytime with those of the evening; of the open air with those of the drawing-room. Thus, in the summer, when the days are long, you will be asked to a pic-nic or an archery party, which will wind up with dancing in-doors, and may even assume the character of a ball. If you are aware of this beforehand, it will always be safe to send your evening dress to your host’s house, and you will learn from the servants whether others have done the same, and whether, therefore, you will not be singular in asking leave to change your costume. But if you are ignorant how the day is to end, you must be guided partly by the hour of invitation, and partly by the extent of your intimacy with the family. I have actually known gentlemen arrive at a large pic-nic at mid-day in complete evening dress, and pitied them with all my heart, compelled as they were to suffer, in tight black clothes, under a hot sun for eight hours, and dance after all in the same dress. On the other hand, if you are asked to come an hour or two before sunset, after six in summer, in the autumn after five, you cannot err by appearing in evening dress. It is always taken as a compliment to do so, and if your acquaintance with your hostess is slight, it would be almost a familiarity to do otherwise. In any case you desire to avoid singularity, so that if you can discover what others who are invited intend to wear, you can always decide on your own attire. In Europe there is a convenient rule for these matters; never appear after four in the afternoon in morning dress; but then gray trousers are there allowed instead of black, and white waistcoats are still worn in the evening. At any rate, it is possible to effect a compromise between the two styles of costume, and if you are likely to be called upon to dance in the evening, it will be well to wear thin boots, a black frock-coat, and a small black neck-tie, and to put a pair of clean white gloves in your pocket. You will thus be at least less conspicuous in the dancing-room than in a light tweed suit.

“Not so the distinction to be made according to size. As a rule, tall men require long clothes—some few perhaps even in the nurse’s sense of those words—and short men short clothes. On the other hand, Falstaff should beware of Jenny Wren coats and affect ample wrappers, while Peter Schlemihl, and the whole race of thin men,{135} must eschew looseness as much in their garments as their morals.

“Lastly we come to what is appropriate to different occasions, and as this is an important subject, I shall treat of it separately. For the present it is sufficient to point out that, while every man should avoid not only extravagance, but even brilliance of dress on ordinary occasions, there are some on which he may and ought to pay more attention to his toilet, and attempt to look gay. Of course, the evenings are not here meant. For evening dress there is a fixed rule, from which we can depart only to be foppish or vulgar; but in morning dress there is greater liberty, and when we undertake to mingle with those who are assembled avowedly for gayety, we should not make ourselves remarkable by the dinginess of our dress. Such occasions are open air entertainments, fêtes, flower-shows, archery-meetings, matinées, and id genus omne, where much of the pleasure to be derived depends on the general effect on the enjoyers, and where, if we cannot pump up a look of mirth, we should, at least, if we go at all, wear the semblance of it in our dress. I have a worthy little friend, who, I believe, is as well disposed to his kind as Lord Shaftesbury himself, but who, for some reason, perhaps a twinge of philosophy about him, frequents the gay meetings to which he is asked in an old coat and a wide-awake. Some people take him for a wit, but he soon shows that he does not aspire to that character; others for a philosopher, but he is too good-mannered for that; others, poor man! pronounce him a cynic, and all are agreed that whatever he may be, he looks out of place, and spoils the general{136} effect. I believe, in my heart, that he is the mildest of men, but will not take the trouble to dress more than once a day. At any rate, he has a character for eccentricity, which, I am sure, is precisely what he would wish to avoid. That character is a most delightful one for a bachelor, and it is generally Cœlebs who holds it, for it has been proved by statistics that there are four single to one married man among the inhabitants of our madhouses; but eccentricity yields a reputation which requires something to uphold it, and even in Diogenes of the Tub it was extremely bad taste to force himself into Plato’s evening party without sandals, and nothing but a dirty tunic on him.

“Another requisite in dress is its simplicity, with which I may couple harmony of color. This simplicity is the only distinction which a man of taste should aspire to in the matter of dress, but a simplicity in appearance must proceed from a nicety in reality. One should not be simply ill-dressed, but simply well-dressed. Lord Castlereagh would never have been pronounced the most distinguished man in the gay court of Vienna, because he wore no orders or ribbons among hundreds decorated with a profusion of those vanities, but because besides this he was dressed with taste. The charm of Brummell’s dress was its simplicity; yet it cost him as much thought, time, and care as the portfolio of a minister. The rules of simplicity, therefore, are the rules of taste. All extravagance, all splendor, and all profusion must be avoided. The colors, in the first place, must harmonize both with our complexion and with one another; perhaps most of all with the color of our hair.{137} All bright colors should be avoided, such as red, yellow, sky-blue, and bright green. Perhaps only a successful Australian gold digger would think of choosing such colors for his coat, waistcoat, or trousers; but there are hundreds of young men who might select them for their gloves and neck-ties. The deeper colors are, some how or other, more manly, and are certainly less striking. The same simplicity should be studied in the avoidance of ornamentation. A few years ago it was the fashion to trim the evening waistcoat with a border of gold lace. This is an example of fashions always to be rebelled against. Then, too, extravagance in the form of our dress is a sin against taste. I remember that long ribbons took the place of neck-ties some years ago. At a commemoration, two friends of mine determined to cut a figure in this matter, having little else to distinguish them. The one wore two yards of bright pink; the other the same quantity of bright blue ribbon, round their necks. I have reason to believe they think now that they both looked superbly ridiculous. In the same way, if the trousers are worn wide, we should not wear them as loose as a Turk’s; or, if the sleeves are to be open, we should not rival the ladies in this matter. And so on through a hundred details, generally remembering that to exaggerate a fashion is to assume a character, and therefore vulgar. The wearing of jewelry comes under this head. Jewels are an ornament to women, but a blemish to men. They bespeak either effeminacy or a love of display. The hand of a man is honored in working, for labor is his mission; and the hand that wears its riches on its fingers, has rarely worked honestly to win them. The best jewel a man can wear is his honor. Let that be bright and shining, well set in prudence, and all others must darken before it. But as we are savages, and must have some silly trickery to hang about us, a little, but very little concession may be made to our taste in this respect. I am quite serious when I disadvise you from the use of nose-rings, gold anklets, and hat-bands studded with jewels; for when I see an incredulous young man of the nineteenth century, dangling from his watch-chain a dozen silly ‘charms’ (often the only ones he possesses), which have no other use than to give a fair coquette a legitimate subject on which to approach to closer intimacy, and which are revived from the lowest superstitions of dark ages, and sometimes darker races, I am quite justified in believing that some South African chieftain, sufficiently rich to cut a dash, might introduce with success the most peculiar fashions of his own country. However this may be, there are already sufficient extravagances prevalent among our young men to attack.

“The man of good taste will wear as little jewelry as possible. One handsome signet-ring on the little finger of the left hand, a scarf-pin which is neither large, nor showy, nor too intricate in its design, and a light, rather thin watch-guard with a cross-bar, are all that he ought to wear. But, if he aspires to more than this, he should observe the following rules:—

“1. Let everything be real and good. False jewelry is not only a practical lie, but an absolute vulgarity, since its use arises from an attempt to appear richer or grander than its wearer is.

{139}“2. Let it be simple. Elaborate studs, waistcoat-buttons, and wrist-links, are all abominable. The last, particularly, should be as plain as possible, consisting of plain gold ovals, with, at most, the crest engraved upon them. Diamonds and brilliants are quite unsuitable to men, whose jewelry should never be conspicuous. If you happen to possess a single diamond of great value you may wear it on great occasions as a ring, but no more than one ring should ever be worn by a gentleman.

“3. Let it be distinguished rather by its curiosity than its brilliance. An antique or bit of old jewelry possesses more interest, particularly if you are able to tell its history, than the most splendid production of the goldsmith’s shop.

“4. Let it harmonize with the colors of your dress.

“5. Let it have some use. Men should never, like women, wear jewels for mere ornament, whatever may be the fashion of Hungarian noblemen, and deposed Indian rajahs with jackets covered with rubies.

“The precious stones are reserved for ladies, and even our scarf-pins are more suitable without them.

“The dress that is both appropriate and simple can never offend, nor render its wearer conspicuous, though it may distinguish him for his good taste. But it will not be pleasing unless clean and fresh. We cannot quarrel with a poor gentleman’s thread-bare coat, if his linen be pure, and we see that he has never attempted to dress beyond his means or unsuitably to his station. But the sight of decayed gentility and dilapidated fashion may call forth our pity, and, at the same time prompt a moral: ‘You have evidently sunken;’ we say to ourselves; ‘But whose fault was it? Am I not led to suppose that the extravagance which you evidently once revelled in has brought you to what I now see you?’ While freshness is essential to being well-dressed, it will be a consolation to those who cannot afford a heavy tailor’s bill, to reflect that a visible newness in one’s clothes is as bad as patches and darns, and to remember that there have been celebrated dressers who would never put on a new coat till it had been worn two or three times by their valets. On the other hand, there is no excuse for untidiness, holes in the boots, a broken hat, torn gloves, and so on. Indeed, it is better to wear no gloves at all than a pair full of holes. There is nothing to be ashamed of in bare hands, if they are clean, and the poor can still afford to have their shirts and shoes mended, and their hats ironed. It is certainly better to show signs of neatness than the reverse, and you need sooner be ashamed of a hole than a darn.

“Of personal cleanliness I have spoken at such length that little need be said on that of the clothes. If you are economical with your tailor, you can be extravagant with your laundress. The beaux of forty years back put on three shirts a day, but except in hot weather one is sufficient. Of course, if you change your dress in the evening you must change your shirt too. There has been a great outcry against colored flannel shirts in the place of linen, and the man who can wear one for three days is looked on as little better than St. Simeon Stylites. I should like to know how often the advocates of linen change their own under-flannel, and whether the same rule does not apply to what is seen as to what is concealed. But while the flannel is perhaps healthier as absorbing the moisture more rapidly, the linen has the advantage of looking cleaner, and may therefore be preferred. As to economy, if the flannel costs less to wash, it also wears out sooner; but, be this as it may, a man’s wardrobe is not complete without half a dozen or so of these shirts, which he will find most useful, and ten times more comfortable than linen in long excursions, or when exertion will be required. Flannel, too, has the advantage of being warm in winter and cool in summer, for, being a non-conductor, but a retainer of heat, it protects the body from the sun, and, on the other hand, shields it from the cold. But the best shirt of all, particularly in winter, is that which wily monks and hermits pretended to wear for a penance, well knowing that they could have no garment cooler, more comfortable, or more healthy. I mean, of course, the rough hair-shirt. Like flannel, it is a non-conductor of heat; but then, too, it acts the part of a shampooer, and with its perpetual friction soothes the surface of the skin, and prevents the circulation from being arrested at any one point of the body. Though I doubt if any of my readers will take a hint from the wisdom of the merry anchorites, they will perhaps allow me to suggest that the next best thing to wear next the skin is flannel, and that too of the coarsest description.

“Quantity is better than quality in linen. Nevertheless it should be fine and well spun. The loose cuff, which we borrowed from the French some four years ago, is a great improvement on the old tight wrist-band, and, indeed, it must be borne in mind that anything{142} which binds any part of the body tightly impedes the circulation, and is therefore unhealthy as well as ungraceful.

“The necessity for a large stock of linen depends on a rule far better than Brummell’s, of three shirts a day, viz:—

“Change your linen whenever it is at all dirty.

“This is the best guide with regard to collars, socks, pocket-handkerchiefs, and our under garments. No rule can be laid down for the number we should wear per week, for everything depends on circumstances. Thus in the country all our linen remains longer clean than in town; in dirty, wet, or dusty weather, our socks get soon dirty and must be changed; or, if we have a cold, to say nothing of the possible but not probable case of tear-shedding on the departure of friends, we shall want more than one pocket-handkerchief per diem. In fact, the last article of modern civilization is put to so many uses, is so much displayed, and liable to be called into action on so many various engagements, that we should always have a clean one in our pockets. Who knows when it may not serve us is in good stead? Who can tell how often the corner of the delicate cambric will have to represent a tear which, like difficult passages in novels is ‘left to the imagination.’ Can a man of any feeling call on a disconsolate widow, for instance, and listen to her woes, without at least pulling out that expressive appendage? Can any one believe in our sympathy if the article in question is a dirty one? There are some people who, like the clouds, only exist to weep; and King Solomon, though not one of them, has given them great encouragement in speaking of the house of mourning. We are bound to weep with them, and we are bound to weep elegantly.

“A man whose dress is neat, clean, simple, and appropriate, will pass muster anywhere.

“A well-dressed man does not require so much an extensive as a varied wardrobe. He wants a different costume for every season and every occasion; but if what he selects is simple rather than striking, he may appear in the same clothes as often as he likes, as long as they are fresh and appropriate to the season and the object. There are four kinds of coats which he must have: a morning-coat, a frock-coat, a dress-coat, and an over-coat. An economical man may do well with four of the first, and one of each of the others per annum. The dress of a gentleman in the present day should not cost him more than the tenth part of his income on an average. But as fortunes vary more than position, if his income is large it will take a much smaller proportion, if small a larger one. If a man, however, mixes in society, and I write for those who do so, there are some things which are indispensable to even the proper dressing, and every occasion will have its proper attire.

“In his own house then, and in the morning, there is no reason why he should not wear out his old clothes. Some men take to the delightful ease of a dressing-gown and slippers; and if bachelors, they do well. If family men, it will probably depend on whether the lady or the gentleman wears the pantaloons. The best walking-dress for a non-professional man is a suit of tweed of the same color, ordinary boots, gloves not too dark for the{144} coat, a scarf with a pin in winter, or a small tie of one color in summer, a respectable black hat and a cane. The last item is perhaps the most important, and though its use varies with fashion, I confess I am sorry when I see it go out. The best substitute for a walking-stick is an umbrella, not a parasol unless it be given you by a lady to carry. The main point of the walking-dress is the harmony of colors, but this should not be carried to the extent of M. de Maltzan, who some years ago made a bet to wear nothing but pink at Baden-Baden for a whole year, and had boots and gloves of the same lively hue. He won his wager, but also the soubriquet of ‘Le Diable enflammé.’ The walking-dress should vary according to the place and hour. In the country or at the sea-side a straw hat or wide-awake may take the place of the beaver, and the nuisance of gloves be even dispensed with in the former. But in the city where a man is supposed to make visits as well as lounge in the street, the frock coat of very dark blue or black, or a black cloth cut-away, the white waistcoat, and lavender gloves, are almost indispensable. Very thin boots should be avoided at all times, and whatever clothes one wears they should be well brushed. The shirt, whether seen or not, should be quite plain. The shirt collar should never have a color on it, but it may be stiff or turned down according as the wearer is Byronically or Brummellically disposed. The scarf, if simple and of modest colors, is perhaps the best thing we can wear round the neck; but if a neck-tie is preferred it should not be too long, nor tied in too stiff and studied a manner. The cane should be extremely simple, a mere stick in fact,{145} with no gold head, and yet for the town not rough, thick, or clumsy. The frock-coat should be ample and loose, and a tall well-built man may throw it back. At any rate, it should never be buttoned up. Great-coats should be buttoned up, of a dark color, not quite black, longer than the frock-coat, but never long enough to reach the ankles. If you have visits to make you should do away with the great-coat, if the weather allows you to do so. The frock-coat, or black cut-away, with a white waistcoat in summer, is the best dress for making calls in.

“It is simple nonsense to talk of modern civilization, and rejoice that the cruelties of the dark ages can never be perpetrated in these days and this country. I maintain that they are perpetrated freely, generally, daily, with the consent of the wretched victim himself, in the compulsion to wear evening clothes. Is there anything at once more comfortless or more hideous? Let us begin with what the delicate call limb-covers, which we are told were the invention of the Gauls, but I am inclined to think, of a much worse race, for it is clearly an anachronism to ascribe the discovery to a Venetian called Piantaleone, and it can only have been Inquisitors or demons who inflicted this scourge on the race of man, and his ninth-parts, the tailors, for I take it that both are equally bothered by the tight pantaloon. Let us pause awhile over this unsightly garment, and console ourselves with the reflection that as every country, and almost every year, has a different fashion in its make of it, we may at last be emancipated from it altogether, or at least be able to wear it à la Turque.

“But it is not all trousers that I rebel against. If{146} I might wear linen appendices in summer, and fur continuations in winter, I would not groan, but it is the evening-dress that inflicts on the man who likes society the necessity of wearing the same trying cloth all the year round, so that under Boreas he catches colds, and under the dog-star he melts. This unmentionable, but most necessary disguise of the ‘human form divine,’ is one that never varies in this country, and therefore I must lay down the rule:—

“For all evening wear—black cloth trousers.

“But the tortures of evening dress do not end with our lower limbs. Of all the iniquities perpetrated under the Reign of Terror, none has lasted so long as that of the strait-jacket, which was palmed off on the people as a ‘habit de compagnie.’ If it were necessary to sing a hymn of praise to Robespierre, Marat, and Co., I would rather take the guillotine as my subject to extol than the swallow tail. And yet we endure the stiffness, unsightliness, uncomfortableness, and want of grace of the latter, with more resignation than that with which Charlotte Corday put her beautiful neck into the ‘trou d’enfer’ of the former. Fortunately modern republicanism has triumphed over ancient etiquette, and the tail-coat of to-day is looser and more easy than it was twenty years ago. I can only say, let us never strive to make it bearable, till we have abolished it. Let us abjure such vulgarities as silk collars, white silk linings, and so forth, which attempt to beautify this monstrosity, as a hangman might wreathe his gallows with roses. The plainer the manner in which you wear your misery, the better.

{147}“Then, again, the black waistcoat, stiff, tight, and comfortless. Fancy Falstaff in a ball-dress such as we now wear. No amount of embroidery, gold-trimmings, or jewel-buttons will render such an infliction grateful to the mass. The best plan is to wear thorough mourning for your wretchedness. In France and America, the cooler white waistcoat is admitted. However, as we have it, let us make the best of it, and not parade our misery by hideous ornamentation. The only evening waistcoat for all purposes for a man of taste is one of simple black, with the simplest possible buttons.

“These three items never vary for dinner-party, muffin-worry, or ball. The only distinction allowed is in the neck-tie. For dinner, the opera, and balls, this must be white, and the smaller the better. It should be too, of a washable texture, not silk, nor netted, nor hanging down, nor of any foppish production, but a simple, white tie, without embroidery. The black tie is admitted for evening parties, and should be equally simple. The shirt-front, which figures under the tie should be plain, with unpretending small plaits. The glove must be white, not yellow. Recently, indeed, a fashion has sprung up of wearing lavender gloves in the evening. They are economical, and as all economy is an abomination, must be avoided. Gloves should always be worn at a ball. At a dinner-party in town they should be worn on entering the room, and drawn off for dinner. While, on the one hand, we must avoid the awkwardness of a gallant sea-captain who, wearing no gloves at a dance, excused himself to his partner by saying, ‘Never mind, miss, I can wash my hands when I’ve done dancing,’{148} we have no need, in the present day, to copy the Roman gentleman mentioned by Athenæus, who wore gloves at dinner that he might pick his meat from the hot dishes more rapidly than the bare-handed guests. As to gloves at tea-parties and so forth, we are generally safer with than without them. If it is quite a small party, we may leave them in our pocket, and in the country they are scarcely expected to be worn; but ‘touch not a cat but with a glove;’ you are always safer with them.

“I must not quit this subject without assuring myself that my reader knows more about it now than he did before. In fact I have taken one thing for granted, viz., that he knows what it is to be dressed, and what undressed. Of course I do not suppose him to be in the blissful state of ignorance on the subject once enjoyed by our first parents. I use the words ‘dressed’ and ‘undressed’ rather in the sense meant by a military tailor, or a cook with reference to a salad. You need not be shocked. I am one of those people who wear spectacles for fear of seeing anything with the naked eye. I am the soul of scrupulosity. But I am wondering whether everybody arranges his wardrobe as our ungrammatical nurses used to do ours, under the heads of ‘best, second-best, third-best,’ and so on, and knows what things ought to be placed under each. To be ‘undressed’ is to be dressed for work and ordinary occupations, to wear a coat which you do not fear to spoil, and a neck-tie which your ink-stand will not object to, but your acquaintance might. To be ‘dressed,’ on the other hand, since by dress we show our respect for society at large, or the{149} persons with whom we are to mingle, is to be clothed in the garments which the said society pronounces as suitable to particular occasions; so that evening dress in the morning, morning dress in the evening, and top boots and a red coat for walking, may all be called ‘undress,’ if not positively ‘bad dress.’ But there are shades of being ‘dressed;’ and a man is called ‘little dressed,’ ‘well dressed,’ and ‘much dressed,’ not according to the quantity but the quality of his coverings.

“To be ‘little dressed,’ is to wear old things, of a make that is no longer the fashion, having no pretension to elegance, artistic beauty, or ornament. It is also to wear lounging clothes on occasions which demand some amount of precision. To be ‘much dressed’ is to be in the extreme of the fashion, with bran new clothes, jewelry, and ornaments, with a touch of extravagance and gaiety in your colors. Thus to wear patent leather boots and yellow gloves in a quiet morning stroll is to be much dressed, and certainly does not differ immensely from being badly dressed. To be ‘well dressed’ is the happy medium between these two, which is not given to every one to hold, inasmuch as good taste is rare, and is a sine quâ non thereof. Thus while you avoid ornament and all fastness, you must cultivate fashion, that is good fashion, in the make of your clothes. A man must not be made by his tailor, but should make him, educate him, give him his own good taste. To be well dressed is to be dressed precisely as the occasion, place, weather, your height, figure, position, age, and, remember it, your means require. It is to be clothed without peculiarity, pretension, or eccentricity; without violent colors, elaborate{150} ornament, or senseless fashions, introduced, often, by tailors for their own profit. Good dressing is to wear as little jewelry as possible, to be scrupulously neat, clean, and fresh, and to carry your clothes as if you did not give them a thought.

“Then, too, there is a scale of honor among clothes, which must not be forgotten. Thus, a new coat is more honorable than an old one, a cut-away or shooting-coat than a dressing-gown, a frock-coat than a cut-away, a dark blue frock-coat than a black frock-coat, a tail-coat than a frock-coat. There is no honor at all in a blue tail-coat, however, except on a gentleman of eighty, accompanied with brass buttons and a buff waistcoat. There is more honor in an old hunting-coat than in a new one, in a uniform with a bullet hole in it than one without, in a fustian jacket and smock-frock than in a frock-coat, because they are types of labor, which is far more honorable than lounging. Again, light clothes are generally placed above dark ones, because they cannot be so long worn, and are, therefore, proofs of expenditure, aliasmoney, which in this world is a commodity more honored than every other; but, on the other hand, tasteful dress is always more honorable than that which has only cost much. Light gloves are more esteemed than dark ones, and the prince of glove-colors is, undeniably, lavender.

“‘I should say Jones was a fast man,’ said a friend to me one day, ‘for he wears a white hat.’ If this idea of my companion’s be right, fastness may be said to consist mainly in peculiarity. There is certainly only one step from the sublimity of fastness to the ridiculousness of{151} snobbery, and it is not always easy to say where the one ends and the other begins. A dandy, on the other hand, is the clothes on a man, not a man in clothes, a living lay figure who displays much dress, and is quite satisfied if you praise it without taking heed of him. A bear is in the opposite extreme; never dressed enough, and always very roughly; but he is almost as bad as the other, for he sacrifices everything to his ease and comfort. The off-hand style of dress only suits an off-hand character. It was, at one time, the fashion to affect a certain negligence, which was called poetic, and supposed to be the result of genius. An ill-tied, if not positively untied cravat was a sure sign of an unbridled imagination; and a waistcoat was held together by one button only, as if the swelling soul in the wearer’s bosom had burst all the rest. If, in addition to this, the hair was unbrushed and curly, you were certain of passing for a ‘man of soul.’ I should not recommend any young gentleman to adopt this style, unless, indeed, he can mouth a great deal, and has a good stock of quotations from the poets. It is of no use to show me the clouds, unless I can positively see you in them, and no amount of negligence in your dress and person will convince me you are a genius, unless you produce an octavo volume of poems published by yourself. I confess I am glad that the négligé style, so common in novels of ten years back, has been succeeded by neatness. What we want is real ease in the clothes, and, for my part, I should rejoice to see the Knickerbocker style generally adopted.

“Besides the ordinary occasions treated of before, there are several special occasions requiring a change{152} of dress. Most of our sports, together with marriage (which some people include in sports), come under this head. Now, the less change we make the better in the present day, particularly in the sports, where, if we are dressed with scrupulous accuracy, we are liable to be subjected to a comparison between our clothes and our skill. A man who wears a red coat to hunt in, should be able to hunt, and not sneak through gates or dodge over gaps. A few remarks on dresses worn in different sports may be useful. Having laid down the rule that a strict accuracy of sporting costume is no longer in good taste, we can dismiss shooting and fishing at once, with the warning that we must not dress well for either. An old coat with large pockets, gaiters in one case, and, if necessary, large boots in the other, thick shoes at any rate, a wide-awake, and a well-filled bag or basket at the end of the day, make up a most respectable sportsman of the lesser kind. Then for cricket you want nothing more unusual than flannel trousers, which should be quite plain, unless your club has adopted some colored stripe thereon, a colored flannel shirt of no very violent hue, the same colored cap, shoes with spikes in them, and a great coat.

“For hunting, lastly, you have to make more change, if only to insure your own comfort and safety. Thus cord-breeches and some kind of boots are indispensable. So are spurs, so a hunting-whip or crop; so too, if you do not wear a hat, is the strong round cap that is to save your valuable skull from cracking if you are thrown on your head. Again, I should pity the man who would attempt to hunt in a frock-coat or a dress-coat; and a scarf with a pin in it is much more convenient than a tie. But beyond these you need nothing out of the common way, but a pocketful of money. The red coat, for instance, is only worn by regular members of a hunt, and boys who ride over the hounds and like to display their ‘pinks.’ In any case you are better with an ordinary riding-coat of dark color, though undoubtedly the red is prettier in the field. If you will wear the latter, see that it is cut square, for the swallow-tail is obsolete, and worn only by the fine old boys who ‘hunted, sir, fifty years ago, sir, when I was a boy of fifteen, sir. Those werehunting days, sir; such runs and such leaps.’ Again, your ‘cords’ should be light in color and fine in quality; your waistcoat, if with a red coat, quite light too; your scarf of cashmere, of a buff color, and fastened with a small simple gold pin; your hat should be old, and your cap of dark green or black velvet, plated inside, and with a small stiff peak, should be made to look old. Lastly, for a choice of boots. The Hessians are more easily cleaned, and therefore less expensive to keep; the ‘tops’ are more natty. Brummell, who cared more for the hunting-dress than the hunting itself, introduced the fashion of pipe-claying the tops of the latter, but the old original ‘mahoganies,’ of which the upper leathers are simply polished, seem to be coming into fashion again.”